To anticipate future losses and preserve economic and financial stability, it is now crucial to mobilize sustainable finance for the adaptation of territories and infrastructures. Hélène Peskine, Deputy Director General and Territorial Network Coordinator at Cerema, actively works to support local authorities and the State in adapting territories to climate change. She shares her expert perspective on the issue._

2024 was the hottest year ever recorded. According to the World Meteorological Organization, it is the first time a calendar year has exceeded the symbolic threshold of +1.5°C compared to the pre-industrial period. The consequences are already visible as 2025 began with two major climate events:

Cyclone Chido hit Mayotte, causing prolonged water outages and requiring emergency evacuations. According to France Assureurs, the amount of compensation paid by insurers amounts to nearly 500 million euros for this single cyclone - with global economic damages of 3.9 billion dollars.

In Los Angeles, devastating fires caused significant human and material losses. Economic damage is estimated at around 150 billion dollars, or 4% of California's annual GDP, according to Jonathan Porter of Accuweather.

As these shocks become systemic, supply chains, critical infrastructure, and financial portfolios become more fragile. The ACPR estimated in 2024 that the French insurance sector could lose 3% of the total value of its assets by 2050 due to global warming. This figure could increase by an additional 0.5% if adaptation and transition actions are carried out late and in a disorganized manner: it is therefore becoming urgent for economic actors to integrate adaptation as a strategic priority.

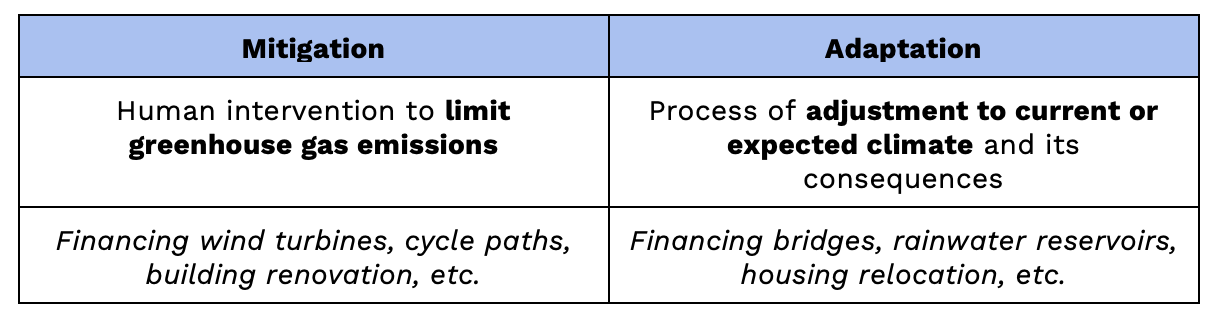

In the fight against climate change, financial actors can intervene at two levels: participating in climate change mitigation or contributing to adaptation to its consequences (In accordance with the definitions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)).

Historically, climate finance flows have largely focused on mitigation. According to the Climate Policy Initiative, only 5% of global climate finance flows were allocated to adaptation in 2021-2022, compared to 95% for mitigation.

Even more revealing: 98% of these adaptation-targeted flows come from public actors and are directed towards development projects. As Hélène Peskine explains, these projects are often perceived as additional costs for local authorities. She describes the example of city center revegetation projects: "_Municipalities must make one-time investment expenditures to set up projects, then pay gardeners who will take care of planting vegetation and caring for it, which constitutes operating expenses. However, the losses avoided thanks to this vegetation during a flood or a heat wave episode will not be taken into account._"

Private capital, meanwhile, is little mobilized. The World Economic Forum offers several explanations:

These obstacles translate into a considerable difference between global investment needs, estimated between 500 billion and 1,300 billion dollars per year by 2030 by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), and the investments actually made, evaluated at only 20.8 billion USD in 2024 by Barclays.

Nevertheless, some financial actors are already aware of the challenge that adaptation represents for the continuity of their activities and are acting now. For example, insurers are already interested in the National Study of Territorial Vulnerability to Floods conducted by CEREMA to feed their data on climate risk, and public investment banks condition their support to local authorities on certain adaptation efforts. Hélène Peskine also tells us that several financial actors are working in partnership with CEREMA to develop a vulnerability indicator enabling them to adapt their risk premiums to climate challenges.

Despite the obstacles it faces, adaptation financing is also characterized by investment opportunities in innovative solutions and resilient infrastructure adapted to extreme events. This is the case with the revegetation of city centers mentioned above, but we can also cite the renovation of water distribution networks to guarantee their efficiency in case of shortages on islands, or the construction of roads and bridges with materials more resilient to landslides in mountainous regions. In France, CEREMA provides technical support to French local authorities in developing these initiatives. At the international level, the United Nations Development Programme on climate change adaptation also accompanies national actors in these projects.

Everything therefore indicates that the adaptation market will experience rapid growth in the coming years. According to Barclays, this market is estimated at 20.8 billion $ in 2024 and should reach 49.2 billion dollars by 2032, more than double. Adaptation therefore represents a potential market to exploit, capable of creating synergies with mitigation: a well-adapted city is also a more sober city.

Although adaptation is still little financed by private capital, several tools exist to encourage their engagement.

The European Union has gradually developed a regulatory framework to direct financial flows towards sustainable activities, with the European Taxonomy as the cornerstone. Since 2023, around a hundred economic activities have been eligible for the climate adaptation objective. However, the alignment rate of private actors remains low, due to the lack of available data, resources allocated to calculating alignment, or investments truly aligned with the adaptation objective.

Green bonds also represent a strategic lever to direct financing towards adaptation projects: hydraulic infrastructure, strengthening of energy networks, coastal protection... At the European level, the European Green Bond Standard mobilizes the European Taxonomy to channel funds towards environmentally sustainable projects. The Climate Bond issued by the City of Paris in 2015, for example, dedicates 20% of the funds raised to adaptation projects. These initiatives include planting 20,000 trees and creating 30 hectares of green spaces to strengthen the city's resilience to heat waves. Green bonds, by allowing the financing of public entities, constitute particularly suitable instruments for directing capital towards the adaptation of territories. Nevertheless, Hélène Peskine nuances: "_Public actors have not really appropriated the European Taxonomy, it is rather a framework designed for private actors_" - which therefore limits its use for adaptation projects largely financed by the public sector.

Similarly, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction published in April 2024 a guide for adaptation and resilience finance, proposing an indicative investment framework. Seven key themes are identified as beneficial to adaptation while being commercially viable: agriculture, cities, health, infrastructure, nature and biodiversity, social solidarity and education, as well as industries and commerce.

Finally, adaptation financing can also rely on partnerships between private investors and public entities. These alliances can take the form of "blended finance." The latter brings together private and public capital within the same financing structure, thus making it possible to mobilize considerable resources while mitigating risks for private actors. Climate Investor 2, managed by Climate Fund Managers, perfectly illustrates this approach: with nearly 875 million dollars mobilized, this fund finances sanitation infrastructure, water management, and coastal adaptation in emerging markets, demonstrating the effectiveness of blended finance for climate adaptation projects. Other frameworks for action also exist: Hélène Peskine describes, for example, the challenges of Territorial Corporate Responsibility (TCR), supported by Duverger, Filippi and Germain, which promotes the territorial anchoring of companies and their collaboration with local actors, as experimented in Lyon and Poitiers.

Adaptation to climate change is therefore a mandatory step to ensure a stable economy, reduce future losses, and create new investment opportunities. Sustainable finance has historically focused on mitigation, but the materialization of physical risks and the evolution of stakeholder expectations are now creating the conditions for a strategic repositioning in favor of adaptation. The climate change adaptation market is only in its infancy, but everything suggests that it is promised a favorable future.